One of the landmark studies that laid the groundwork for the use of medications to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) was the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS).1 All participants in the study had elevated IOP at baseline, and the investigators were able to conclude that IOP was a good predictor of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) onset.1 Despite this, there are patients who suffer from a unique form of glaucoma that seems to contradict what the OHTS trial says about the pathogenesis of the disease. These patients demonstrate that glaucoma is not actually caused by high pressure, but by compromised perfusion of the optic nerve and retinal nerve fibers, commonly exacerbated by high IOP.

Normal-tension glaucoma (NTG) is an enigma of a disease that has spurred much deliberation, eventually culminating in the Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS). This landmark trial attempted to bring clarity to the pressure debate.2 Although slower rates of visual field loss were noted in cases where IOP was lowered 30% or more, nearly half of the untreated participants had no disease progression at 5-year follow-up. This was attributed to the slowly progressing nature of the disease itself.2 Ultimately, investigators concluded that the natural course of NTG should be assessed before initiating IOP therapy, especially when taking into account the postsurgical cataracts that often complicate IOP-lowering surgeries.2 These results prompted further consideration of whether trabeculectomy was the best course of action in patients with NTG, where IOP levels fail to paint the full picture of the disease.

Observing Risk Factors for Glaucoma

Managing NTG requires looking at risk factors rather than tonometry readings. This can include shifting the spotlight away from IOP and toward circulation. Many conditions that compromise perfusion of the optic nerve, such as chronic hypotension and arrhythmias, have been hypothesized to play a role in NTG.3 The CNTGS has also supplemented this train of thought by noting optic disc hemorrhage and migraine headaches as certain IOP-independent risk factors that influenced NTG progression.2 Other studies have demonstrated an association between NTG and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA), which is characterized by abnormal nocturnal breathing due to transient obstruction of the upper airway.4 The intermittent vascular compromise during apneic episodes may contribute to optic nerve hypoperfusion, which is hypothesized as a potential mechanism for the pathogenesis of NTG.4 This makes intuitive sense: what good is optimizing the perfusion pressure gradient when the supply of oxygen to the entire body is compromised because of OSA? It might not matter what a patient’s IOP is if oxygen is not even reaching their circulation.

Often, glaucoma specialists do not consider managing glaucoma patients’ secondary risk factors, such as OSA, unless the simpler target, high IOP, is not an option. It could be possible that optimizing secondary risk factors in parallel with addressing IOP lowering could benefit patients with either POAG or NTG. Obstructive sleep apnea is a “low-hanging fruit” that also happens to have a cheap, quick, and convenient screening tool that can be performed on every patient in glaucoma clinics.

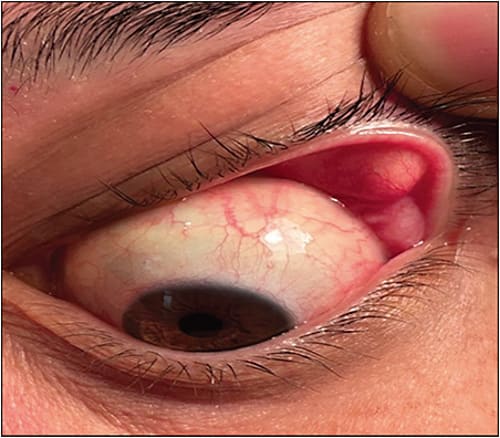

Diagnosing OSA typically involves polysomnography, which generates an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). The AHI value is positively correlated with disease severity, and it has been shown to be elevated in patients with NTG.5 These findings highlight the importance of incorporating OSA screening within standard visits to the ophthalmologist, especially considering its notorious history of being underdiagnosed. Although glaucoma specialists are not typically going to perform polysomnography, OSA can present with floppy eyelid syndrome (FES) (Figure 1), which can easily be assessed in the glaucoma clinic and will be described further below. In addition, some basic questions that could be asked at the office include the following:

- Do you snore?

- Do you ever stop breathing at night?

- Do you feel tired during the day?

- Do you have high blood pressure?

Based on the patient’s responses to these questions, ophthalmologists can refer to the most appropriate providers for further workup, potentially helping NTG and POAG patients alike. This approach should be coupled with maintaining active dialogue with primary care providers to assess for adequate follow-up of IOP-independent risk factors for progression.

Although studies have revealed an association between OSA and NTG, OSA is also regularly diagnosed in POAG patients. A recent study that investigated the relationship between OSA and high-pressure glaucoma phenotypes revealed a higher prevalence of OSA in POAG and ocular hypertension (OHT) than in NTG.6 Latent disease processes could be lurking for patients being started on therapy for glaucoma. Further investigation into the association between OSA and glaucoma progression may help reveal insights into why certain patients fail to respond to pharmacologic therapy and why some individuals progress more rapidly than others. These are the questions that pose a conundrum for the glaucoma community, leading to much deliberation as to what comorbidities must be taken into consideration when assessing patients. With this in mind, it can be reasonably argued that OSA screening should be incorporated into all glaucoma patient consultations.In-office Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

A very convenient additional screening tool is at the fingertips of every ophthalmologist measuring IOPs after instilling proparacaine. Obstructive sleep apnea has been shown to copresent with another ocular phenomenon known as FES, which is described as a laxity of the upper eyelids that contributes to chronic palpebral conjunctivitis.7 This condition is widely underdiagnosed, which is unfortunate considering the fact that some studies suggest up to 90% of patients with FES also have OSA.7 The diagnosis of FES is made clinically by noting effortless eversion of the eyelid (Figure 1). Anecdotally, we have found that asking about sleep apnea when I notice easily everted lids commonly yields an affirmative response. If patients already know they have sleep apnea, we remind them how important it is to be compliant with treatment (usually continuous positive airway pressure machines). Aside from eye manifestations associated with FES (fine papillary reaction of the tarsal conjunctival, and punctate epithelial defects with fluorescein staining8) there are many sobering statistics for those patients hesitant to start, or for those noncompliant with treatment. Research has found associations between OSA and hypertension, depression, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality.9 As few as 40% of OSA patients have been diagnosed according to a 2015 review on the consequences of untreated sleep apnea.10

The strong overlap between OSA and FES justifies screening during periodic vision exams to help facilitate early detection of NTG. When IOPs are unremarkable, some of these risk factors and associated conditions can help ophthalmologists find a treatment target. However, glaucoma specialists should not neglect the same risk factors in the majority of glaucoma patients with POAG and other high-pressure glaucoma phenotypes.

Conclusion

Glaucoma patients who have FES should be queried about sleep apnea. Assessing patients for FES is a useful clinical tool that could help many glaucoma patients discover a modifiable risk factor. Initiating treatment for OSA can help their prognosis for glaucoma progression while dramatically improving their health overall. GP

References

- Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):714-830. doi:10.1001/archopht.120.6.714

- Mercer R, Mathew RG, Henein C. Infographic: Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS). Eye (Lond). 2021;35(10):2667-2668. doi:10.1038/s41433-021-01431-2

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Normal tension glaucoma. EyeWiki. Accessed July 29, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Normal_Tension_Glaucoma#cite_note-ntgsg18-18

- Bilgin G. Normal-tension glaucoma and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a prospective study. BMC Ophthalmology. 2014;14(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-14-27

- Chuang LH, Koh YY, Chen HSL, et al. Normal tension glaucoma in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a structural and functional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(13):e19468. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019468

- Bahr K, Bopp M, Kewader W, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in a monocentric pilot study. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):258. doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01533-7

- Cristescu Teodor R, Mihaltan FD. Eyelid laxity and sleep apnea syndrome: a review. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2019;63(1):2-9.

- Din N, Vasquez-Perez A, Ezra DG, Tuft SJ. Serious corneal complications and undiagnosed floppy eyelid syndrome: a case series and a 10-year retrospective review. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(2):225-228. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.03.003

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Peppard PE, Nieto FJ, Hla KM. Burden of sleep apnea: rationale, design, and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. WMJ. 2009;108(5):246-249.

- Knauert M, Naik S, Gillespie MB, Kryger M. Clinical consequences and economic costs of untreated obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;1(1):17-27. doi:10.1016/j.wjorl.2015.08.001