Medicare payment rates for physicians have declined by 2.8% for 2025. As a practical matter, physicians and administrators must look for solutions to offset this loss. One possibility is spending less time charting in the medical record and using the saved time to see additional patients.

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) was implemented on January 1, 1992. Subsequently, the definitions of evaluation and management (E/M) CPT codes (992xx) changed dramatically. Emphasis was placed on specific criteria in the medical record for history of present illness, review of systems, medical history, and exam elements. Detailed checklists were inaugurated.

Electronic medical record (EMR) systems organized these elements with pick lists of potential responses. Physicians learned that more documentation led to higher reimbursement. Chart notes grew more voluminous but not necessarily more useful. “Code creep,” or changing medical records to increase reimbursement, grew in subtle and pernicious ways.1

On January 1, 2021, new E/M documentation guidelines and coding criteria were promulgated by the American Medical Association to reduce administrative burden, support patient care within teams, make code selection more accurate, and place emphasis on medical decision-making instead of checklists of chart elements. The notes within the assessment and plan are paramount, whereas the rest of the chart documentation for the history and exam is described as “medically appropriate” and left to the physician’s discretion.

Time Is Money

Since the 2021 major revision in E/M documentation guidelines and code selection criteria, physician behavior has not changed much because their electronic medical records continue to use a lot of boxes. That is by design, because an EMR functions as a database of elements, and boxes define the pieces. Scribes and medical assistants take histories, make chart entries, click boxes, and copy notes from earlier visits. The volume of notes hasn’t diminished much. Yet all the time and effort spent charting is expensive in terms of personnel cost.

Let’s do the math. In a typical ophthalmologist’s office, there are about 140 office visits per week. If you saved just 1 minute per office visit, or about 7% of the time spent on each exam, this would permit you to add 11 more exams per week. That represents more than $50,000 per year in revenue. By itself, that’s enough to offset the cuts in Medicare reimbursement for 2025.

Simple But Effective Charts

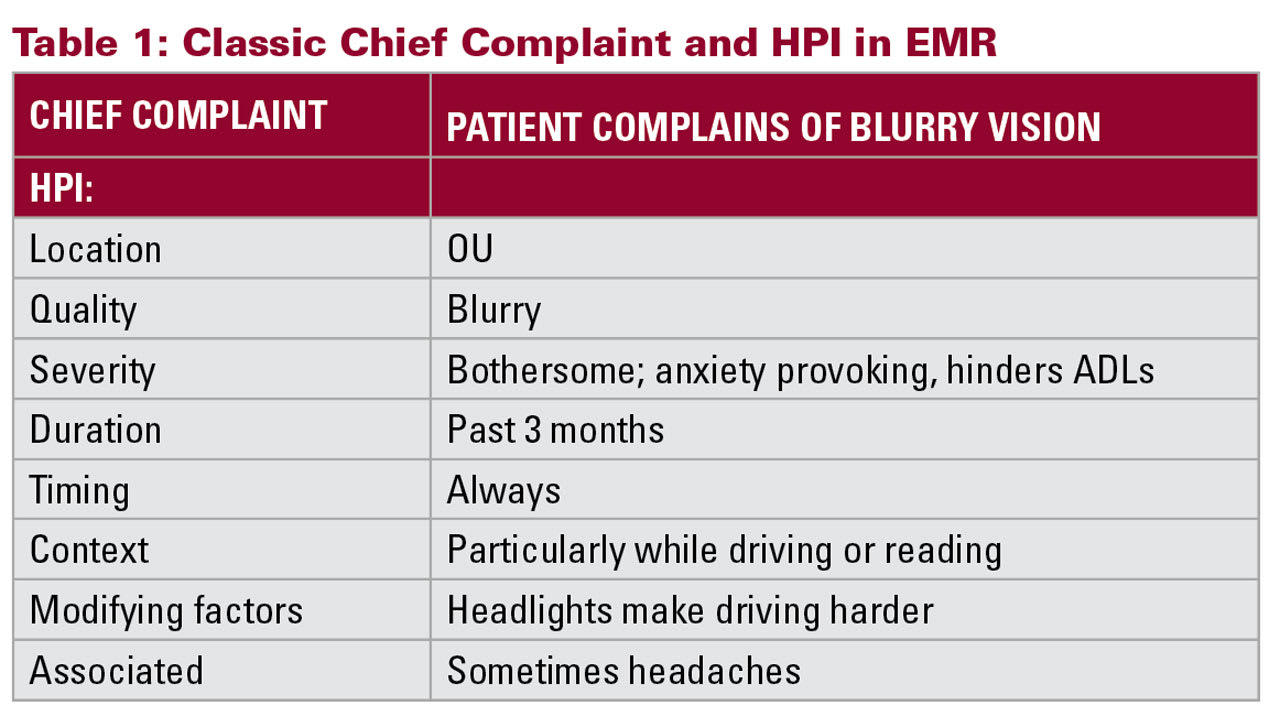

Reducing the number of entries in the chart without diminishing its value is the key. Simplifying the first part of the medical record begins with combining the chief complaint and history of present illness (HPI). Table 1 illustrates an enumerated HPI distinct from the chief complaint.

A quicker, shorter version that combines the chief complaint and HPI is, “Patient complains of blurry vision OU and headaches for ≈3 months, especially driving or reading.”

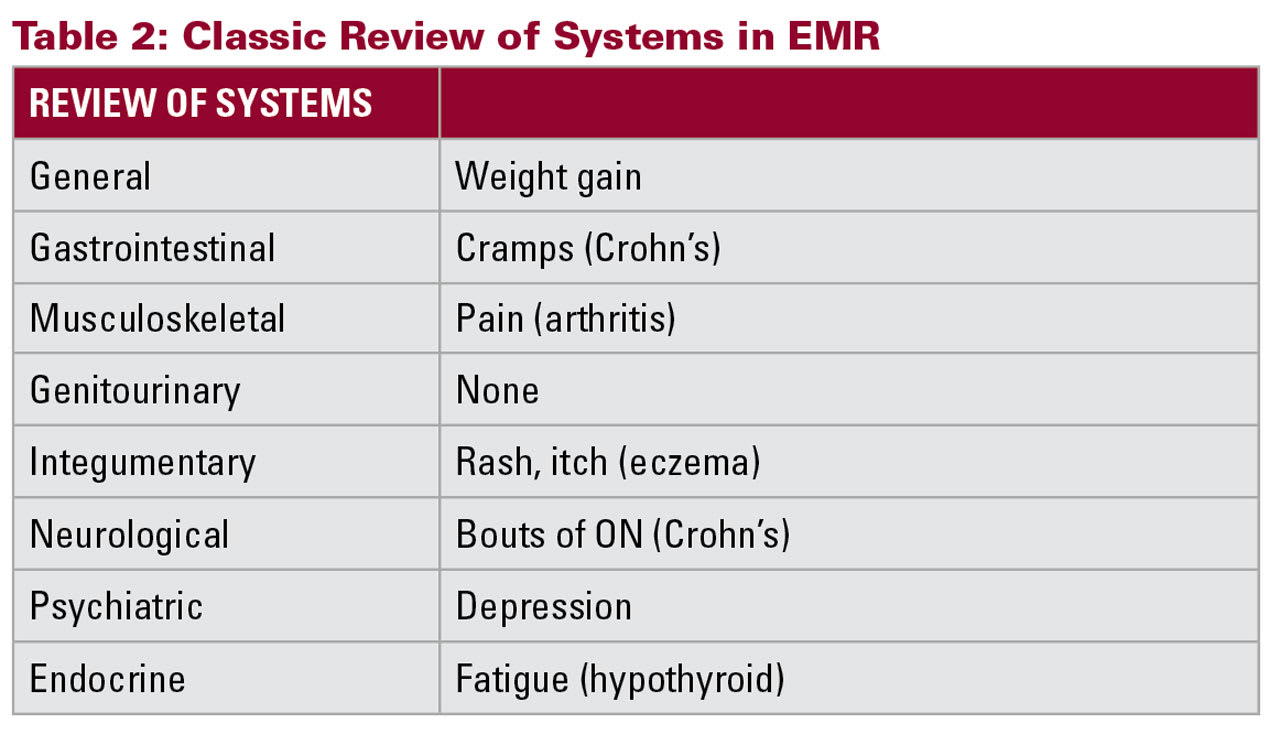

Table 2 is a classic tabulated review of systems common in many EMR systems. A compressed review of systems, with only pertinent points relevant to the ophthalmologist, might omit some of these elements and use fewer words such as: “Crohn’s, arthritis, eczema, and hypothyroid.”

While compressing some parts of the chart note, the sections devoted to assessment and plan merit more attention, detail, and a longer note. In this section, record all the conditions that were addressed during the encounter. The number of conditions addressed and their severity and stability, along with the treatment plan(s), determine the level of the E/M service for most eye exams. For example, in a glaucoma recheck your chart notes should include:

- The type of glaucoma

- The stage of the glaucoma

- The affected eye(s)

- Disease progression (if any)

- Disparity between the eyes

- Comorbid disease(s)

- Interactions between glaucoma and comorbid disease(s)

- Medication use and compliance

- Tolerance to medication or adverse reactions to them

- Alternative therapies considered and discussed with the patient

- Orders for tests; and

- Schedule for follow-up visit.

An abbreviated note such as “glaucoma OU, RTO 4 mos” is weak and barely describes the thought process in medical decision making.

Other Considerations

Up to this point, this discussion has focused on E/M codes. Yet, ophthalmologists and optometrists still use eye codes (920xx) frequently. Eye codes are found more often with routine eye care for ametropias. They still require specific elements and are not driven by medical decision-making. The CPT code description of eye codes already provides physician discretion for the medical history, so there is not much potential time saved in that area of the chart documentation.

Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) collects information related to quality measures from physicians. When physicians elect to use their electronic medical record system in concert with a registry to gather information for MIPS, that information is independent of billing and coding requirements. Any effort to limit data in the medical record to save time should not hazard your parallel efforts to comply with MIPS. Ring-fencing MIPS data elements is an important consideration as you strive for greater efficiency and time savings. GP

Reference

1. Seiber EE. Physician code creep: evidence in Medicaid state employee health insurance billing. Health Care Financing Review. Summer 2007. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/07summerpg83pdf